Saturday, June 30, 2012

Jay Brannan

Jay Brannan (b. 1982) is a Texas born singer, actor, and songwriter. An openly gay tenor who plays folk/pop acoustic guitar, he has forged a career based on the strength of his intimate YouTube videos and self promotion.

After a brief stint at the University of Cincinnati’s acting school, he moved on to Los Angeles and ultimately to New York City, where he was cast in the 2006 film Shortbus, directed by John Cameron Mitchell. He won the part, which required him to perform an explicit sex scene, by submitting an audition tape. Brannan also contributed a song to the film’s soundtrack, Soda Shop, which was his first professionally recorded track.

Brannan subsequently produced an EP and acted in Holding Trevor (2007) as the promiscuous best friend of the protagonist. Since then, he has toured and released two well-received albums. He has achieved cult status among gay men. Since 2008 he has been able to support himself from earnings from his concerts and music sales. His second album, In Living Cover (2009), reached number ten on the Billboard Top Heatseekers chart for the week of July 25, 2009. Brannan promoted the album in an interview on ABC News Now in July, 2009.

Jay’s newest video is a departure from his shy persona. "Rob Me Blind" delves into the frustrating experience of "missed connections." Instead of reticence and missed opportunity, Jay acts on his impulses. In this video he exchanges flirtatious glances with a stranger while waiting for an elevator. As the doors open at each new floor, Brannan plays out a scene in which he imagines their future life together.

"I'm way too shy to ever approach anyone on the street, on the subway, in an elevator or even at a bar," Brannan says, "so it was fun to make a video involving chemistry-at-first-sight, where the characters didn't just end up going home to check the 'missed connections' listings on Craigslist."

After completing a tour of Australia this weekend, Brannan begins a US tour July 18 in Boston, ending August 25 in NYC (Highline Ballroom). The complete tour covers 28 cities, a radical departure for Brannan, who typically tours only 4-10 cities at a time. It’s a true sign of his increasing stature and popularity.

Complete tour details here:

http://jaybrannan.com/tour

Thursday, June 28, 2012

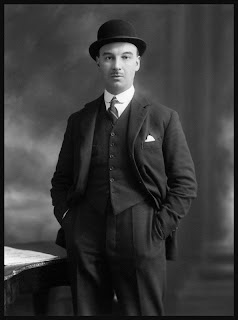

Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs

German-born activist Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs (1825-1895), was a 19th-century pioneer of the modern gay rights movement. He had his first homosexual experience with his riding instructor at the age of fourteen, although he later wrote that as a child he had frequently worn girls’ clothes and wanted to be a girl. He went on to university, from which he graduated with degrees in law and theology, after which he studied history. He then worked as an official legal adviser for a district court in northwest Germany (Hanover), but he was dismissed when his homosexuality became open knowledge.

At the age of thirty-seven he told his family and friends that he was sexually attracted to men, and he went on to write a series of essays based on his research about variations of human sexuality, specifically gender identities and sexual orientations.

Five years later Ulrichs became the first gay man to speak out publicly in defense of homosexuality when he pleaded at the Congress of German Jurists in Munich for a resolution urging the repeal of anti-homosexual laws. He was shouted down. Two years later, in 1869, the Austrian writer Karl-Maria Kertbeny coined the word "homosexual", and from the 1870s the subject of sexual orientation began to be widely discussed.

In 1864 his books were confiscated and banned by police in Saxony. Later the same thing happened in Berlin, and his works were banned throughout Prussia. Some of these papers were recently found in the Prussian state archives and were subsequently published in 2004. Several of Ulrichs's important works are now back in print, both in German and translated editions.

When Prussia annexed Hannover, Ulrichs moved to Munich and then on to Stuttgart and Würzburg (this blogger’s university city). After publishing the twelfth volume of his human sexuality research findings, he entered into self-imposed exile in central Italy. He continued to write prolifically and publish his works at his own expense. In 1895, he received an honorary diploma from the University of Naples. A short time thereafter he died of kidney failure, just a few weeks shy of his seventieth birthday. He is buried in his chosen city of exile, L’Aquila (Italy); a ceremony at his recently restored grave is shown in the photograph below.

Marquis Niccolò Persichetti, who gave the eulogy at his funeral, spoke these words: But with your loss, oh Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs, the fame of your works and your virtue will not likewise disappear ... but rather, as long as intelligence, virtue, learning, insight, poetry and science are cultivated on this earth and survive the weakness of our bodies, as long as the noble prominence of genius and knowledge are rewarded, we and those who come after us will shed tears and scatter flowers on your venerated grave.

Late in life Ulrichs himself wrote: Until my dying day I will look back with pride that I found the courage to come face to face in battle against the spectre which for time immemorial has been injecting poison into me and into men of my nature. Many have been driven to suicide because all their happiness in life was tainted. Indeed, I am proud that I found the courage to deal the initial blow to the hydra of public contempt.

Forgotten for many years, Ulrichs has recently become a cult figure in Europe. There are streets named for him in Munich, Bremen and Hanover (photo above); his birthday is marked each year by a street party and poetry reading at Karl-Heinrich-Ulrichs-Platz in Munich. The city of L'Aquila has restored his grave and hosts an annual pilgrimage to the civic cemetery at noon every August 26. Subsequent gay rights advocates were aware of their debt to Ulrichs, and Magnus Hirschfeld referenced Ulrichs in his 1914 work, The Homosexuality of Men and Women. As well, the International Lesbian and Gay Law Association presents an annual Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs Award in his memory.

Trivia: Ulrichs penned the first known gay vampire story, titled "Manor" in his book Sailor Stories (Matrosengeschichten).

At the age of thirty-seven he told his family and friends that he was sexually attracted to men, and he went on to write a series of essays based on his research about variations of human sexuality, specifically gender identities and sexual orientations.

Five years later Ulrichs became the first gay man to speak out publicly in defense of homosexuality when he pleaded at the Congress of German Jurists in Munich for a resolution urging the repeal of anti-homosexual laws. He was shouted down. Two years later, in 1869, the Austrian writer Karl-Maria Kertbeny coined the word "homosexual", and from the 1870s the subject of sexual orientation began to be widely discussed.

In 1864 his books were confiscated and banned by police in Saxony. Later the same thing happened in Berlin, and his works were banned throughout Prussia. Some of these papers were recently found in the Prussian state archives and were subsequently published in 2004. Several of Ulrichs's important works are now back in print, both in German and translated editions.

When Prussia annexed Hannover, Ulrichs moved to Munich and then on to Stuttgart and Würzburg (this blogger’s university city). After publishing the twelfth volume of his human sexuality research findings, he entered into self-imposed exile in central Italy. He continued to write prolifically and publish his works at his own expense. In 1895, he received an honorary diploma from the University of Naples. A short time thereafter he died of kidney failure, just a few weeks shy of his seventieth birthday. He is buried in his chosen city of exile, L’Aquila (Italy); a ceremony at his recently restored grave is shown in the photograph below.

Late in life Ulrichs himself wrote: Until my dying day I will look back with pride that I found the courage to come face to face in battle against the spectre which for time immemorial has been injecting poison into me and into men of my nature. Many have been driven to suicide because all their happiness in life was tainted. Indeed, I am proud that I found the courage to deal the initial blow to the hydra of public contempt.

Forgotten for many years, Ulrichs has recently become a cult figure in Europe. There are streets named for him in Munich, Bremen and Hanover (photo above); his birthday is marked each year by a street party and poetry reading at Karl-Heinrich-Ulrichs-Platz in Munich. The city of L'Aquila has restored his grave and hosts an annual pilgrimage to the civic cemetery at noon every August 26. Subsequent gay rights advocates were aware of their debt to Ulrichs, and Magnus Hirschfeld referenced Ulrichs in his 1914 work, The Homosexuality of Men and Women. As well, the International Lesbian and Gay Law Association presents an annual Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs Award in his memory.

Trivia: Ulrichs penned the first known gay vampire story, titled "Manor" in his book Sailor Stories (Matrosengeschichten).

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Merle Miller

The newspaper received more than 2,000 letters in response, setting a record. As a result, the article was expanded and published as a book – On Being Different. What It Means To Be a Homosexual (1971) – making Miller a spokesman for the gay movement.

Both the newspaper article and book represented a tremendous leap forward, because they did much to humanize the homosexual’s predicament. During the next ten months much of the correspondence that Miller received was from gay readers who wrote things along the lines of “Nothing I have ever read has helped as much to restore my own self-respect” and “so much of what you have to say I have experienced myself and have rarely been able to trust anyone to ‘let go’.”

Some straight readers realized for the first time that “homosexuals were people, too, with feelings, just like anybody else.” One reader, who had always blanched at bigoted labels such as kike, Dago, spic and nigger wrote, “Yet for every time I've said homosexual, I've said ‘fag’ a thousand times. You've made me wonder how I could have believed that I had modeled my life on the dignity of man while being so cruel, so thoughtless to so many.”

The mother of a gay son wrote to Merle Miller: “Being a nice human being, my son is accepted by people everywhere. Above all, as he grows older he knows his family loves him always. Families of young gay men should not treat them as ‘sick’. Different, yes – but not sick. I think we’d have fewer suicides and better adjusted ‘different’ males if the family unit stayed close to these boys. The whole problem in our generation is that we worry so much about what our neighbors think...” At the time it was radical thinking that a parent's proper role might be to accept a child's sexual orientation, and Miller’s article paved the way for this turn around in philosophy.

As a bookish boy who wore thick glasses and played the violin and piano, Miller had been called a sissy when he started school. He said, “I heard that word at least five days a week for the next 13 years until I skipped town and went away to college.” At the University of Iowa, he wrote a satirical column in the Daily Iowan and had a job as a radio commentator. In 1938 Miller won a scholarship to study at the BBC in London.

During World War II Miller was combat correspondent and editor of the European edition of Yank – The Army Weekly. He later worked as an editor at Time and Harper’s magazines and wrote frequently for The New York Times and Esquire magazine. He was a book reviewer for The Saturday Review of Literature and a contributing editor for The Nation. As well, his work appeared frequently in The New York Times Magazine. From 1947-1951 Miller was married to Eleanor Green, who worked for publisher Farrar-Straus.

Miller’s postwar career as a television script writer and novelist was interrupted by inclusion on Senator Joseph McCarthy’s "Blacklist." In 1962 he was hired to write the script for a proposed TV series on ex-President Harry Truman. Miller spent hundreds of hours with Truman, but major networks didn’t show interest in airing the documentary. Miller felt one of the reasons it was never shown on TV was because he had been a blacklisted writer. Miller once again stirred up controversy in 1967, when he signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest,” vowing to refuse to pay taxes raised to fund the Vietnam War.

In 1974 Miller published Plain Speaking, a book based on his interviews with Truman, and it landed in the number one spot on the New York Times best seller list and remained on the list for over a year. This success led to two best-selling biographies on presidents Eisenhower and Johnson.

Merle Miller (center) with Truman Library director Benedict Zobrist (left) and Milton Perry, Truman Library curator, at the library in 1974.

Sunday, June 24, 2012

Lord Berners

Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson (1883-1950)

The fourteenth Baron Berners was an eccentric British aristocratic man of leisure, who was also a painter, diplomat, chef, novelist and composer of classical music. Above all an aesthete, his contemporaries described him as short, bald and witty, a “mixture of sweetness and malice.”

He was born in into a family with a long noble pedigree. As a shy and effeminate only child, he was discouraged from advancing his love of art and music by a pious, staid mother, who felt such pursuits were unbecoming to a man of his class. Instead, she desired, more than anything, for him to become skilled at horsemanship. The eccentricities Berners displayed started early in life. Once, upon hearing that you could teach a dog to swim by throwing him into water, young Gerald concluded that by throwing his mother's dog out the window, he could teach it to fly. After being punished as a small boy by being closed up in a cupboard, he retaliated by locking all the bathrooms in his parent’s house and throwing the keys into a pond.

Berners was educated at Eton and entered the diplomatic service in 1899, despite failing the qualifying examinations. Among his assets, however, were fluency in both Italian and German. He was first posted as an honorary attaché to the British Embassy in Constantinople and was subsequently stationed in Rome, where he became a friend of author Ronald Firbank and composer Igor Stravinsky, who admired his musical efforts.

In 1918 Gerald inherited his uncle's title, fortune, and properties at the age of 35. Consequently, he left the diplomatic service and retired to an estate at Faringdon, twelve miles west of Oxford, in order to devote his life entirely to the pursuit of his pastimes and pleasures. Berners bought Faringdon House, a Palladian style manor, in 1919 and gave it to his mother for her lifetime use, keeping only modest quarters for himself. He spent most of the 1920s in London leading an amiably flamboyant existence, while also keeping a house in Italy.

With the death of both his mother and stepfather in 1931, the Faringdon manor house caught his imagination. Because it was more accurately described as comfortable than glamorous, Berners set about transforming it, creating a masterpiece of an English country house. On the walls Berners hung important paintings by Corot, Constable and Matisse. The 54-ft. drawing-room afforded fine views through five French windows beyond the fountain to one of the longest vistas in England, extending 22 miles across a patchwork English landscape.

As Lord Berners, Gerald cultivated a well-deserved reputation as an eccentric. When he was not dabbling in composing music, writing or painting (which he called “my little hobbies”), he read an enormous amount. He was known for such antics as dyeing the doves on his estate various colors, arranging color-coordinated meals (more often than not the food and dove colors matched), and traveling across Europe with a fold-away piano keyboard in the rear seat of his Rolls-Royce. He also frequented many of the literary and artistic salons of the day, and counted Evelyn Waugh, Cecil Beaton, the Mitford sisters and the Sitwells among his friends and guests. He once invited a friend’s Arabian stallion to join them in the drawing-room for afternoon tea. I’m not making this up.

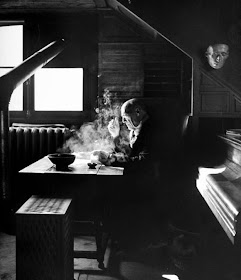

Lord Berners (above) in the drawing room of Faringdon House, painting a portrait of his favorite horse, which had been brought into the room for the occasion.

The list of oddball behavior goes on. He sent the following invitation to Sybil Colefax, noted for her aggressive social climbing:

“I wonder if by any chance you are free to dine tomorrow night? It is only a tiny party for Winston and GBS*. I think it important they should get together at this moment. There will be no one else except for Toscanini and myself. Do please forgive this terribly short notice.”

The cruel joke was that Berners made both his name and the address on the envelope completely illegible.

*George Bernard Shaw

Even while entertaining extravagantly, Berners still found time to pursue his various artistic careers. As a composer, he was largely self-taught; nonetheless, he produced a body of work that Stravinsky praised. Berners was also friends with composer Sir William Walton, and Walton dedicated his popular Belshazzar's Feast to him. His best known and most enduring works, however, are his ballets, particularly The Triumph of Neptune (1926), commissioned and produced by Diaghilev and choreographed by Balanchine. His ballet A Wedding Bouquet (1936) had placards containing words penned by Gertrude Stein (shown with Berners at right). Lord Berners also commissioned Stein to write an opera libretto for Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights, but he never got around to composing music for it. As well, Berners wrote the soundtrack for the 1947 film Nicholas Nickleby.

Berners also wrote three volumes of autobiography and a number of short, campy Firbankian novels. In the 1930s Berners enjoyed a brief vogue as a painter, and his landscapes sold for extraordinary prices.

For twenty years, Berners lived openly with a man thirty years his junior, the equally eccentric Robert “Mad Boy” Heber-Percy (1911-1986). Before taking up with Lord Berners, Heber-Percy flunked a career in the cavalry, acted as a Hollywood extra, was sacked as a waiter for sloshing soup over a customer and helped run a notorious London nightclub. In 1934, Berners had a "folly" tower, perhaps the last such structure built in England, erected on his estate as a birthday present for his "Mad Boy." When asked what purpose the 140-ft. tower served he explained, “The great point of the tower is that it will be entirely useless.” A notice at the entrance read: "Members of the Public committing suicide from this tower do so at their own risk.” Despite Heber-Percy's short-lived wartime marriage to a woman, Berners left him his manor house (Faringdon House, c. 1780), his estate and fortune upon his death on April 19, 1950. “Mad Boy” Heber-Percy lived there himself until his death in 1986. It is now owned by Heber-Percy’s granddaughter, who is based in Rome. Faringdon Manor is available for rent by the month; recently a Texas couple took up residence there for a year.

When it came to food, Lord Berners was a masterful host, and his superb meals were sometimes overwhelmingly luxurious. One of Lord Berners’ best known dishes, Roast Chicken in Cream, was even included in The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book (1954), an immensely entertaining memoir/recipe compilation.

Berners died at sixty-six, a fairly peaceful death, not in the least fearful of what lay beyond. The doctor who had attended Lord Berners during his last years refused to send a bill, saying that the pleasure of his company had been payment enough. All his life Lord Berners had lived on the strength of his charm.

Baron Berners’ epitaph on his gravestone reads:

Here lies Lord Berners

One of the learners

His great love of learning

May earn him a burning

But praise to the Lord

He seldom was bored

Most of the information for this post comes from Mark Amory’s biography, “Lord Berners: The Last Eccentric” (1998).

There is a good deal to be said for frivolity. Frivolous people, when all is said and done, do less harm in the world than some of our philanthropists and reformers. Mistrust a man who never has an occasional flash of silliness. - Lord Berners

The fourteenth Baron Berners was an eccentric British aristocratic man of leisure, who was also a painter, diplomat, chef, novelist and composer of classical music. Above all an aesthete, his contemporaries described him as short, bald and witty, a “mixture of sweetness and malice.”

He was born in into a family with a long noble pedigree. As a shy and effeminate only child, he was discouraged from advancing his love of art and music by a pious, staid mother, who felt such pursuits were unbecoming to a man of his class. Instead, she desired, more than anything, for him to become skilled at horsemanship. The eccentricities Berners displayed started early in life. Once, upon hearing that you could teach a dog to swim by throwing him into water, young Gerald concluded that by throwing his mother's dog out the window, he could teach it to fly. After being punished as a small boy by being closed up in a cupboard, he retaliated by locking all the bathrooms in his parent’s house and throwing the keys into a pond.

Berners was educated at Eton and entered the diplomatic service in 1899, despite failing the qualifying examinations. Among his assets, however, were fluency in both Italian and German. He was first posted as an honorary attaché to the British Embassy in Constantinople and was subsequently stationed in Rome, where he became a friend of author Ronald Firbank and composer Igor Stravinsky, who admired his musical efforts.

In 1918 Gerald inherited his uncle's title, fortune, and properties at the age of 35. Consequently, he left the diplomatic service and retired to an estate at Faringdon, twelve miles west of Oxford, in order to devote his life entirely to the pursuit of his pastimes and pleasures. Berners bought Faringdon House, a Palladian style manor, in 1919 and gave it to his mother for her lifetime use, keeping only modest quarters for himself. He spent most of the 1920s in London leading an amiably flamboyant existence, while also keeping a house in Italy.

With the death of both his mother and stepfather in 1931, the Faringdon manor house caught his imagination. Because it was more accurately described as comfortable than glamorous, Berners set about transforming it, creating a masterpiece of an English country house. On the walls Berners hung important paintings by Corot, Constable and Matisse. The 54-ft. drawing-room afforded fine views through five French windows beyond the fountain to one of the longest vistas in England, extending 22 miles across a patchwork English landscape.

As Lord Berners, Gerald cultivated a well-deserved reputation as an eccentric. When he was not dabbling in composing music, writing or painting (which he called “my little hobbies”), he read an enormous amount. He was known for such antics as dyeing the doves on his estate various colors, arranging color-coordinated meals (more often than not the food and dove colors matched), and traveling across Europe with a fold-away piano keyboard in the rear seat of his Rolls-Royce. He also frequented many of the literary and artistic salons of the day, and counted Evelyn Waugh, Cecil Beaton, the Mitford sisters and the Sitwells among his friends and guests. He once invited a friend’s Arabian stallion to join them in the drawing-room for afternoon tea. I’m not making this up.

Lord Berners (above) in the drawing room of Faringdon House, painting a portrait of his favorite horse, which had been brought into the room for the occasion.

The list of oddball behavior goes on. He sent the following invitation to Sybil Colefax, noted for her aggressive social climbing:

“I wonder if by any chance you are free to dine tomorrow night? It is only a tiny party for Winston and GBS*. I think it important they should get together at this moment. There will be no one else except for Toscanini and myself. Do please forgive this terribly short notice.”

The cruel joke was that Berners made both his name and the address on the envelope completely illegible.

*George Bernard Shaw

Even while entertaining extravagantly, Berners still found time to pursue his various artistic careers. As a composer, he was largely self-taught; nonetheless, he produced a body of work that Stravinsky praised. Berners was also friends with composer Sir William Walton, and Walton dedicated his popular Belshazzar's Feast to him. His best known and most enduring works, however, are his ballets, particularly The Triumph of Neptune (1926), commissioned and produced by Diaghilev and choreographed by Balanchine. His ballet A Wedding Bouquet (1936) had placards containing words penned by Gertrude Stein (shown with Berners at right). Lord Berners also commissioned Stein to write an opera libretto for Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights, but he never got around to composing music for it. As well, Berners wrote the soundtrack for the 1947 film Nicholas Nickleby.

Berners also wrote three volumes of autobiography and a number of short, campy Firbankian novels. In the 1930s Berners enjoyed a brief vogue as a painter, and his landscapes sold for extraordinary prices.

For twenty years, Berners lived openly with a man thirty years his junior, the equally eccentric Robert “Mad Boy” Heber-Percy (1911-1986). Before taking up with Lord Berners, Heber-Percy flunked a career in the cavalry, acted as a Hollywood extra, was sacked as a waiter for sloshing soup over a customer and helped run a notorious London nightclub. In 1934, Berners had a "folly" tower, perhaps the last such structure built in England, erected on his estate as a birthday present for his "Mad Boy." When asked what purpose the 140-ft. tower served he explained, “The great point of the tower is that it will be entirely useless.” A notice at the entrance read: "Members of the Public committing suicide from this tower do so at their own risk.” Despite Heber-Percy's short-lived wartime marriage to a woman, Berners left him his manor house (Faringdon House, c. 1780), his estate and fortune upon his death on April 19, 1950. “Mad Boy” Heber-Percy lived there himself until his death in 1986. It is now owned by Heber-Percy’s granddaughter, who is based in Rome. Faringdon Manor is available for rent by the month; recently a Texas couple took up residence there for a year.

When it came to food, Lord Berners was a masterful host, and his superb meals were sometimes overwhelmingly luxurious. One of Lord Berners’ best known dishes, Roast Chicken in Cream, was even included in The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book (1954), an immensely entertaining memoir/recipe compilation.

Berners died at sixty-six, a fairly peaceful death, not in the least fearful of what lay beyond. The doctor who had attended Lord Berners during his last years refused to send a bill, saying that the pleasure of his company had been payment enough. All his life Lord Berners had lived on the strength of his charm.

Baron Berners’ epitaph on his gravestone reads:

Here lies Lord Berners

One of the learners

His great love of learning

May earn him a burning

But praise to the Lord

He seldom was bored

Most of the information for this post comes from Mark Amory’s biography, “Lord Berners: The Last Eccentric” (1998).

There is a good deal to be said for frivolity. Frivolous people, when all is said and done, do less harm in the world than some of our philanthropists and reformers. Mistrust a man who never has an occasional flash of silliness. - Lord Berners

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

Liberace

Just a few years ago during a visit to Las Vegas I was astonished to learn that a gay twenty-something violinist in our group had never heard of Liberace (pronounced Libber-AH-chee). We hoofed it over to the Liberace museum (since closed), where a fabulous collection of costumes, bejeweled pianos and automobiles, all of dubious taste, was displayed in a strip mall once owned by the pianist. The docents played it straight – no mention was made of the gay scandals and controversies that littered the last years of the entertainer’s life.

Liberace (1919-1987) was a classically trained pianist who was bullied while in his early teens growing up in Wisconsin. He had a speech impediment and shunned athletic activity for a fondness for playing the piano and cooking. At the age of twenty he played Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, for which he received strong reviews. However, it was his experience playing popular music during the Depression years that put money in his pocket, and he soon became addicted to the luxuries those gigs afforded. He decided to abandon a career as a serious concert pianist and instead focused on the entertainment aspects of his performances.

He hit his stride in the 1950s, becoming an entertainment phenomenon through wildly popular television appearances, night club performances and recordings. For the next twenty years he was the highest paid entertainer in the world. Throughout the 1970s and early 80s he was earning $300,000 a week in Las Vegas. He typically spoke to the audience and even sang while sporting ever more over-the-top costumes and jewelry. His piano performances, which were highly embellished and shortened versions of classical standards (he called it classical music with the boring parts left out), became secondary to the glitz and outrageous props, and pop tunes became increasingly important elements of his repertoire. Liberace’s signature prop was a candelabra placed atop whatever piano he was playing. Liberace once stated, "I don't give concerts, I put on a show."

His private life was as flamboyant as his stage presence. He collected homes that he furnished in his favored Baroque and Rococo style, with gaudy accessories crowding every horizontal surface.

Liberace denied that he was gay his entire life, even as he was dying of AIDS. A much younger Scott Thorson (above left), who was employed as a “chauffeur/assistant”, was Liberace’s lover for a number of years. Liberace lavished the young man with gifts of luxury cars and costly jewelry. In 1982 24-year-old Thorson sued 63-year-old Liberace for palimony, an act that fueled a tabloid scandal. Thorson, who had undergone plastic surgery to look more like a younger Liberace (is this sick, or what?), had been cast aside for a teenaged male; Thorson himself had been seduced by Liberace when he was sixteen. The suit was ultimately settled out of court for a paltry $95,000 cash payment to Thorson, without Liberace admitting guilt. Thorson later admitted that being dismissed in 1982 may have saved his life, since Liberace was HIV-positive and symptomatic from 1985. In a 2011 interview, actress and close friend Betty White confirmed that Liberace was gay, and that she often served as a beard to counter rumors of his homosexuality.

The melodrama that marked Liberace’s last years is being revived in HBO Films’ upcoming biopic titled “Behind the Candelabra.” Michael Douglas will portray the tortured closeted gay entertainer Liberace in his first post-cancer role; Mr. Douglas received a stage 4 throat cancer diagnosis in 2010. The biopic, which will air in 2013, is being scripted by Richard LaGravenese and will be directed by Steven Soderbergh.

Rob Lowe will play Liberace’s plastic surgeon, and Scott Bakula will play the choreographer who introduced Liberace to his much younger longtime partner Scott Thorson, a pivotal role to be played by Matt Damon. They complete a cast that includes Dan Aykroyd as Liberace’s manager and Debbie Reynolds as Liberace’s mother Frances. Cheyenne Jackson has just this week joined the cast, but is not yet at liberty to announce which role he will play. Marvin Hamlish will provide the score.

Production of the film, which is based on Scott Thorson’s 1988 book “Behind the Candelabra: My Life with Liberace,” will begin next month in Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Palm Springs, where Liberace maintained homes.

A typical stage costume for Liberace's flamboyant performances. This sequins and fur trimmed caped number is from a Christmas show.

Liberace (1919-1987) was a classically trained pianist who was bullied while in his early teens growing up in Wisconsin. He had a speech impediment and shunned athletic activity for a fondness for playing the piano and cooking. At the age of twenty he played Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, for which he received strong reviews. However, it was his experience playing popular music during the Depression years that put money in his pocket, and he soon became addicted to the luxuries those gigs afforded. He decided to abandon a career as a serious concert pianist and instead focused on the entertainment aspects of his performances.

He hit his stride in the 1950s, becoming an entertainment phenomenon through wildly popular television appearances, night club performances and recordings. For the next twenty years he was the highest paid entertainer in the world. Throughout the 1970s and early 80s he was earning $300,000 a week in Las Vegas. He typically spoke to the audience and even sang while sporting ever more over-the-top costumes and jewelry. His piano performances, which were highly embellished and shortened versions of classical standards (he called it classical music with the boring parts left out), became secondary to the glitz and outrageous props, and pop tunes became increasingly important elements of his repertoire. Liberace’s signature prop was a candelabra placed atop whatever piano he was playing. Liberace once stated, "I don't give concerts, I put on a show."

His private life was as flamboyant as his stage presence. He collected homes that he furnished in his favored Baroque and Rococo style, with gaudy accessories crowding every horizontal surface.

Liberace denied that he was gay his entire life, even as he was dying of AIDS. A much younger Scott Thorson (above left), who was employed as a “chauffeur/assistant”, was Liberace’s lover for a number of years. Liberace lavished the young man with gifts of luxury cars and costly jewelry. In 1982 24-year-old Thorson sued 63-year-old Liberace for palimony, an act that fueled a tabloid scandal. Thorson, who had undergone plastic surgery to look more like a younger Liberace (is this sick, or what?), had been cast aside for a teenaged male; Thorson himself had been seduced by Liberace when he was sixteen. The suit was ultimately settled out of court for a paltry $95,000 cash payment to Thorson, without Liberace admitting guilt. Thorson later admitted that being dismissed in 1982 may have saved his life, since Liberace was HIV-positive and symptomatic from 1985. In a 2011 interview, actress and close friend Betty White confirmed that Liberace was gay, and that she often served as a beard to counter rumors of his homosexuality.

The melodrama that marked Liberace’s last years is being revived in HBO Films’ upcoming biopic titled “Behind the Candelabra.” Michael Douglas will portray the tortured closeted gay entertainer Liberace in his first post-cancer role; Mr. Douglas received a stage 4 throat cancer diagnosis in 2010. The biopic, which will air in 2013, is being scripted by Richard LaGravenese and will be directed by Steven Soderbergh.

Rob Lowe will play Liberace’s plastic surgeon, and Scott Bakula will play the choreographer who introduced Liberace to his much younger longtime partner Scott Thorson, a pivotal role to be played by Matt Damon. They complete a cast that includes Dan Aykroyd as Liberace’s manager and Debbie Reynolds as Liberace’s mother Frances. Cheyenne Jackson has just this week joined the cast, but is not yet at liberty to announce which role he will play. Marvin Hamlish will provide the score.

Production of the film, which is based on Scott Thorson’s 1988 book “Behind the Candelabra: My Life with Liberace,” will begin next month in Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Palm Springs, where Liberace maintained homes.

A typical stage costume for Liberace's flamboyant performances. This sequins and fur trimmed caped number is from a Christmas show.

Sunday, June 17, 2012

Jim Parsons

Television’s “Big Bang Theory” star Jim Parsons plays the lead in a new Broadway production of "Harvey," the 1944 Pulitzer Prize-winning play by Mary Chase that opened Thursday night in New York. The two-time Emmy winner and Golden Globe Award winner Parsons tackles the role of Elwood P. Dowd, made known to millions in a 1950 cinematic portrayal by Jimmy Stewart. Harvey is the name of Dowd’s best friend, a six-foot tall invisible rabbit, and the relationship between the two is what drives this comedy of errors.

In last month’s profile in The New York Times, the actor discussed his recent small role in Larry Kramer’s "The Normal Heart" and his current Broadway run as the star of "Harvey." Though Parsons hadn't previously commented on his personal life, the article mentioned that Parsons is gay and in a committed relationship with his partner. Parsons will return to his Emmy winning role as the socially clueless Dr. Sheldon Cooper on "The Big Bang Theory" for its sixth season on CBS. Meanwhile, he is using his summer hiatus from television to return to the stage.

The casting of Parsons in the iconic role of Elwood P. Dowd follows the recent celebrity casting trend that guarantees full houses in the risky world of stage productions. Teenagers leaving a performance of "The Normal Heart" excitedly exclaimed that they chose to see that particular play because of “Sheldon,” using the name of the character Parsons plays on television. They had not known that the play was about men dying of AIDS. In "Harvey," Parsons is leading a Broadway cast for the first time.

Jim has enjoyed a 20-year career since his first high school stage roles. He is a graduate of the Old Globe/University of San Diego Masters of Fine Arts program, and his time there was spent studying and performing Shakespeare and the classics.

“I cannot say, and I mean this quite sincerely, how often my time at grad school at USD enters my mind,” says Parsons. “The type of work I did in that program to get through some of those Shakespearean texts is very similar to the work strategy I use to get through these scientifically dense speeches,” referencing his job playing Sheldon, a formula-spouting, pop-culture-pontificating theoretical physicist on TV.

Growing up in Houston, Parsons was a theater nerd from the start. The actor recalls his role of the Kola-Kola bird in his first-grade production of Kipling’s “The Elephant’s Child.” In the NYT profile, Parsons related that his curiosity about performance grew from watching the physical antics and reaction shots in the television sitcom “Three’s Company.”

Jim Parsons took on roles in more than two dozen plays during and after his undergraduate years at the University of Houston. After his classical theater training at the University of San Diego he spent several years working Off-Broadway while making guest appearances on TV. His role as Sheldon in “The Big Bang Theory” changed everything, transforming him into a star. He seems to handle his celebrity well, and his professional confidence led to last month’s public revelations about his personal live in the NYT profile. It was surely one of the most casual coming-out stories anyone can recall, delivered with little more drama than a yawn. All reference to his sexual orientation took up exactly one sentence in the lengthy profile. I quote in full:

“ ‘The Normal Heart’ resonated with him on a few levels: Mr. Parsons is gay and in a 10-year relationship, and working with an ensemble again on stage was like nourishment, he said.”

I think it’s no small triumph that a major TV star can come out in such a relaxed fashion. The expected splash across the covers of supermarket tabloids never materialized. Jim's partner is Todd Spiewak (above), who is an advertising agency art director. The couple has appeared together publicly at numerous entertainment award shows and sporting events.

Parsons will leave his role in "Harvey" on Broadway in August to return to “The Big Bang Theory.”

In last month’s profile in The New York Times, the actor discussed his recent small role in Larry Kramer’s "The Normal Heart" and his current Broadway run as the star of "Harvey." Though Parsons hadn't previously commented on his personal life, the article mentioned that Parsons is gay and in a committed relationship with his partner. Parsons will return to his Emmy winning role as the socially clueless Dr. Sheldon Cooper on "The Big Bang Theory" for its sixth season on CBS. Meanwhile, he is using his summer hiatus from television to return to the stage.

The casting of Parsons in the iconic role of Elwood P. Dowd follows the recent celebrity casting trend that guarantees full houses in the risky world of stage productions. Teenagers leaving a performance of "The Normal Heart" excitedly exclaimed that they chose to see that particular play because of “Sheldon,” using the name of the character Parsons plays on television. They had not known that the play was about men dying of AIDS. In "Harvey," Parsons is leading a Broadway cast for the first time.

Jim has enjoyed a 20-year career since his first high school stage roles. He is a graduate of the Old Globe/University of San Diego Masters of Fine Arts program, and his time there was spent studying and performing Shakespeare and the classics.

“I cannot say, and I mean this quite sincerely, how often my time at grad school at USD enters my mind,” says Parsons. “The type of work I did in that program to get through some of those Shakespearean texts is very similar to the work strategy I use to get through these scientifically dense speeches,” referencing his job playing Sheldon, a formula-spouting, pop-culture-pontificating theoretical physicist on TV.

Growing up in Houston, Parsons was a theater nerd from the start. The actor recalls his role of the Kola-Kola bird in his first-grade production of Kipling’s “The Elephant’s Child.” In the NYT profile, Parsons related that his curiosity about performance grew from watching the physical antics and reaction shots in the television sitcom “Three’s Company.”

Jim Parsons took on roles in more than two dozen plays during and after his undergraduate years at the University of Houston. After his classical theater training at the University of San Diego he spent several years working Off-Broadway while making guest appearances on TV. His role as Sheldon in “The Big Bang Theory” changed everything, transforming him into a star. He seems to handle his celebrity well, and his professional confidence led to last month’s public revelations about his personal live in the NYT profile. It was surely one of the most casual coming-out stories anyone can recall, delivered with little more drama than a yawn. All reference to his sexual orientation took up exactly one sentence in the lengthy profile. I quote in full:

“ ‘The Normal Heart’ resonated with him on a few levels: Mr. Parsons is gay and in a 10-year relationship, and working with an ensemble again on stage was like nourishment, he said.”

I think it’s no small triumph that a major TV star can come out in such a relaxed fashion. The expected splash across the covers of supermarket tabloids never materialized. Jim's partner is Todd Spiewak (above), who is an advertising agency art director. The couple has appeared together publicly at numerous entertainment award shows and sporting events.

Parsons will leave his role in "Harvey" on Broadway in August to return to “The Big Bang Theory.”

Friday, June 15, 2012

Michael Feinstein

When twenty-year-old Michael Feinstein, best known as the ambassador of the American Song book, was introduced to lyricist Ira Gershwin by the widow of the concert pianist-actor Oscar Levant, his life was changed forever. Feinstein became Gershwin's assistant for six years, archiving the extensive Gershwin works and gaining unprecedented access to unpublished Gershwin songs, which he went on to perform and record.

Discovered by Liza Minnelli, his career took off after his 1986 Broadway show, Isn't It Romantic. Through his live performances, recordings, film and television appearances, he has become one of the premiere interpreters of American popular song. As well, he has collaborated on song writing with the likes of Alan and Marilyn Bergman, Lindy Robbins and Carole Bayer Sager. He specializes in popular songs from the 1930s and ‘40s and is at his best in cabaret venues, using the intimacy of these settings to create an emotional bond with his audiences.

Working as a piano salesman in Los Angeles in the late 1970s, he supplemented his income by singing and playing in local nursing homes. While browsing in a record store he came across some recordings by Oscar Levant and contacted his widow June, who introduced him to Ira Gershwin. After cataloging the collection of musical materials, Feinstein became Gershwin’s literary executor. Feinstein then began performing in small West Hollywood clubs and for private parties, leading up to a sensational run in NYC at the Algonquin Hotel’s famed Oak Room. These days he has his own nightclub in New York, Feinstein’s at Loews Regency Hotel, a throwback to the classic era of supper clubs.

He created controversy by performing at the White House Valentine’s Day gathering in 2006 for President Bush and a gathering of right-wing Republicans. Feinstein responded to criticism from the gay community: “My acceptance of the invitation was with the understanding that I would bring my partner. We were treated in every way as a couple – both our names were on the invitatins, and we had our photographs taken with the President and First Lady. We introduced ourselves to other guests as life partners and were accepted without issue as a couple. The White House belongs to all of us.”

Feinstein and his partner of 15 years, Terrence Flannery, were married in 2008 by Judge Judy in Los Angeles. The ceremony took place on the couple's estate before more than a hundred of their close friends, including Warren Beatty, Annette Bening, David Hyde Pierce, Doris Roberts, Joan Collins and Henry Winkler, all of who were entertained by Liza Minnelli and Barry Manilow.

In 2009 he collaborated with Cheyenne Jackson on an acclaimed supper club act The Power of Two, which they then took to Carnegie Hall with a 17-piece orchestra in late 2010. Jackson created a sensation in Act I with the Gershwins’ Someone to Watch Over Me. After dedicating the song to his partner Monte Lapka, Jackson sat down on the lip of the Carnegie Hall stage (channeling Judy Garland’s performance there) and quipped to a front-row patron: “Pardon my crotch.”

We Kiss in a Shadow (1951 – Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I)

Duet with Cheyenne Jackson; the lyrics take on new meaning when sung by two gay men.

We kiss in a shadow, we hide from the moon,

Our meetings are few and over too soon.

We speak in a whisper, afraid to be heard;

When people are near, we speak not a word.

Alone in our secret, together we sigh, For one smiling day to be free to kiss in the sunlight

And say to the sky: "Behold and believe what you see! Behold how my lover loves me!"

His PBS television series, Michael Feinstein: Man on a Mission, aired for two seasons. It was a tribute to classic American music that followed him around the country as he preserved, performed and explored that music. As well, the Michael Feinstein Great American Songbook Initiative opened its offices last year. Its mission is to bring the music of the Great American Songbook to today’s young people and to preserve it for generations to come. In this video clip Feinstein performs a Gershwin medley:

Discovered by Liza Minnelli, his career took off after his 1986 Broadway show, Isn't It Romantic. Through his live performances, recordings, film and television appearances, he has become one of the premiere interpreters of American popular song. As well, he has collaborated on song writing with the likes of Alan and Marilyn Bergman, Lindy Robbins and Carole Bayer Sager. He specializes in popular songs from the 1930s and ‘40s and is at his best in cabaret venues, using the intimacy of these settings to create an emotional bond with his audiences.

Working as a piano salesman in Los Angeles in the late 1970s, he supplemented his income by singing and playing in local nursing homes. While browsing in a record store he came across some recordings by Oscar Levant and contacted his widow June, who introduced him to Ira Gershwin. After cataloging the collection of musical materials, Feinstein became Gershwin’s literary executor. Feinstein then began performing in small West Hollywood clubs and for private parties, leading up to a sensational run in NYC at the Algonquin Hotel’s famed Oak Room. These days he has his own nightclub in New York, Feinstein’s at Loews Regency Hotel, a throwback to the classic era of supper clubs.

He created controversy by performing at the White House Valentine’s Day gathering in 2006 for President Bush and a gathering of right-wing Republicans. Feinstein responded to criticism from the gay community: “My acceptance of the invitation was with the understanding that I would bring my partner. We were treated in every way as a couple – both our names were on the invitatins, and we had our photographs taken with the President and First Lady. We introduced ourselves to other guests as life partners and were accepted without issue as a couple. The White House belongs to all of us.”

Feinstein and his partner of 15 years, Terrence Flannery, were married in 2008 by Judge Judy in Los Angeles. The ceremony took place on the couple's estate before more than a hundred of their close friends, including Warren Beatty, Annette Bening, David Hyde Pierce, Doris Roberts, Joan Collins and Henry Winkler, all of who were entertained by Liza Minnelli and Barry Manilow.

In 2009 he collaborated with Cheyenne Jackson on an acclaimed supper club act The Power of Two, which they then took to Carnegie Hall with a 17-piece orchestra in late 2010. Jackson created a sensation in Act I with the Gershwins’ Someone to Watch Over Me. After dedicating the song to his partner Monte Lapka, Jackson sat down on the lip of the Carnegie Hall stage (channeling Judy Garland’s performance there) and quipped to a front-row patron: “Pardon my crotch.”

We Kiss in a Shadow (1951 – Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I)

Duet with Cheyenne Jackson; the lyrics take on new meaning when sung by two gay men.

We kiss in a shadow, we hide from the moon,

Our meetings are few and over too soon.

We speak in a whisper, afraid to be heard;

When people are near, we speak not a word.

Alone in our secret, together we sigh, For one smiling day to be free to kiss in the sunlight

And say to the sky: "Behold and believe what you see! Behold how my lover loves me!"

His PBS television series, Michael Feinstein: Man on a Mission, aired for two seasons. It was a tribute to classic American music that followed him around the country as he preserved, performed and explored that music. As well, the Michael Feinstein Great American Songbook Initiative opened its offices last year. Its mission is to bring the music of the Great American Songbook to today’s young people and to preserve it for generations to come. In this video clip Feinstein performs a Gershwin medley:

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Gareth Thomas

Welsh rugby sporting legend Gareth "Alfie" Thomas came out in 2009, while still an active player. He had captained Wales in 2005 to their first Grand Slam victory since 1978. He had one of the fiercest reputations on the field – and a row of missing front teeth to prove it.

He married in 2002, but confessed the truth about his sexual orientation to his devastated wife in 2006, unable to cope with the guilt of deceiving her. They soon separated. He spilled his long-kept secret to a coach and felt a huge wave of relief after living a lie for almost 20 years.

Astonishingly, his team mates offered support; their reaction was basically, “We don’t care. Why didn’t you tell us sooner?” Thomas said, “No one distanced himself from me – not one single person.” He continued to play as an openly gay athlete. Although he retired from international rugby in late 2007, he went on playing with the Cardiff Blues.

By 2009 he made the bold decision to go public. He felt attitudes had changed, and the time was right for sport to start accepting openly gay people as other professions had in recent years. He didn’t want young gay athletes to have to hide in the closet to suffer in silence, too terrified to tell anyone.

“I'm not going on a crusade, but I'm proud of who I am. I feel I have achieved everything I could ever possibly have hoped to achieve out of rugby, and I did it being gay. I want to send a positive message to other gay athletes that they can do it, too.”

At age 17 he realized that he wasn't attracted to women the way his teammates were, but he was unwilling to accept it. He made up stories about sexual conquests with women to fit in with the overly-macho world of rugby players. He sometimes got into fights to affirm his masculinity, thus cementing the ruse. His first sexual experience with a man (a non-rugby player) left him feeling ashamed and afraid. During his marriage he sometimes gave in to his same-sex urges when his team was on the road. The guilt was crippling. Reaching the breaking point emotionally and psychologically, he at last confessed his secret to his wife. She tried to be understanding, but realized that her husband’s feelings for men would never dissipate. They separated, but remained firm friends based on their honest feelings for each other.

“I don't want to be known as a gay rugby player. I am a rugby player first and foremost. I am a man who just happens to be gay. It's irrelevant. What I choose to do when I close the door at home has nothing to do with what I have achieved in rugby.”

Of late Thomas has become an in demand representative for gay activism, and he started a hot line for young people who are grappling with their sexuality. He has become a positive role model working against stereotypes.

One of Gareth's more revealing moments:

Astonishingly, his team mates offered support; their reaction was basically, “We don’t care. Why didn’t you tell us sooner?” Thomas said, “No one distanced himself from me – not one single person.” He continued to play as an openly gay athlete. Although he retired from international rugby in late 2007, he went on playing with the Cardiff Blues.

By 2009 he made the bold decision to go public. He felt attitudes had changed, and the time was right for sport to start accepting openly gay people as other professions had in recent years. He didn’t want young gay athletes to have to hide in the closet to suffer in silence, too terrified to tell anyone.

“I'm not going on a crusade, but I'm proud of who I am. I feel I have achieved everything I could ever possibly have hoped to achieve out of rugby, and I did it being gay. I want to send a positive message to other gay athletes that they can do it, too.”

At age 17 he realized that he wasn't attracted to women the way his teammates were, but he was unwilling to accept it. He made up stories about sexual conquests with women to fit in with the overly-macho world of rugby players. He sometimes got into fights to affirm his masculinity, thus cementing the ruse. His first sexual experience with a man (a non-rugby player) left him feeling ashamed and afraid. During his marriage he sometimes gave in to his same-sex urges when his team was on the road. The guilt was crippling. Reaching the breaking point emotionally and psychologically, he at last confessed his secret to his wife. She tried to be understanding, but realized that her husband’s feelings for men would never dissipate. They separated, but remained firm friends based on their honest feelings for each other.

“I don't want to be known as a gay rugby player. I am a rugby player first and foremost. I am a man who just happens to be gay. It's irrelevant. What I choose to do when I close the door at home has nothing to do with what I have achieved in rugby.”

Of late Thomas has become an in demand representative for gay activism, and he started a hot line for young people who are grappling with their sexuality. He has become a positive role model working against stereotypes.

One of Gareth's more revealing moments:

Sunday, June 10, 2012

André Gide

"Believe those who are seeking the truth.

Doubt those who find it."

French writer André Gide (1869-1951) was the first openly gay man to receive the Nobel Prize for literature. In 1947, at age 78, Gide was too ill to travel to Stockholm to receive the prize. Considered a controversial literary figure his entire life, Gide was nevertheless honored for his novels, essays, travel diaries and commentaries on contemporary events when his award was placed in the hands of the French Ambassador.

Born in Paris into a Protestant family, Gide’s first publication was a novella in 1891, when he was twenty-two. Great works followed, such as The Immoralist (1902) and Strait Is the Gate (1909), books which cemented his literary stature. However, the publication of Corydon (1920), his nonfiction work in praise of homosexuality, sent his reputation into a nosedive, and Gide was almost universally condemned. Five years later The Counterfeiters (1925), considered by many his best novel, brought renewed recognition and acceptance. With the publication of Travels in the Congo (1927), an attack on French colonialism, Gide’s influence took on a new dimension.

"It is better to be hated for what you are than to be loved for something you are not."

The publication of his autobiography If It Die (1926) left the reading public in shock with its salacious details of homosexual lovemaking as a teenager under the dining table with the concierge’s son and as an adult atop the sand dunes with an Arab youth in Algeria.

Gide met up with Oscar Wilde and his lover Lord Alfred Douglas while in North Africa, and their friendship influenced his subsequent writings, which exalted honesty, openness and sincerity. Gide was one of the few people willing to defend Wilde’s literary reputation in the years after the Englishman’s death.

"One does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time."

In 1916 at the age of forty seven Gide fell in love with 16-year-old Marc Allégret (in photo at right), whom he adopted, and the couple eloped to London to commence an eleven year relationship. Marc was to fall briefly under the spell of Jean Cocteau, whom Gide feared would "corrupt" him. After the notorious affair with Gide, Allégret went on to establish a successful career in cinema, becoming a noted screenwriter and director of more than 50 films.

“My faith in communism is like my faith in religion: it is a promise of salvation for mankind. If I have to lay my life down that it may succeed, I would do so without hesitation.”

As a distinguished writer sympathizing with the cause of communism, Gide was invited to tour the Soviet Union as a guest of the Soviet Union of Writers. The tour disillusioned him, however, and he subsequently became quite critical of Soviet Communism.

“It is impermissible under any circumstances for morals to sink as low as communism has done. No one can begin to imagine the tragedy of humanity, of morality, of religion and of freedoms in the land of communism, where man has been debased beyond belief.”

Gide lived in North Africa during WW II and soon thereafter returned from Tunisia to Paris, where he died in 1951 at the age of 81. The following year the Catholic church included all of his literary works on the index of Forbidden Books.

Doubt those who find it."

French writer André Gide (1869-1951) was the first openly gay man to receive the Nobel Prize for literature. In 1947, at age 78, Gide was too ill to travel to Stockholm to receive the prize. Considered a controversial literary figure his entire life, Gide was nevertheless honored for his novels, essays, travel diaries and commentaries on contemporary events when his award was placed in the hands of the French Ambassador.

Born in Paris into a Protestant family, Gide’s first publication was a novella in 1891, when he was twenty-two. Great works followed, such as The Immoralist (1902) and Strait Is the Gate (1909), books which cemented his literary stature. However, the publication of Corydon (1920), his nonfiction work in praise of homosexuality, sent his reputation into a nosedive, and Gide was almost universally condemned. Five years later The Counterfeiters (1925), considered by many his best novel, brought renewed recognition and acceptance. With the publication of Travels in the Congo (1927), an attack on French colonialism, Gide’s influence took on a new dimension.

"It is better to be hated for what you are than to be loved for something you are not."

The publication of his autobiography If It Die (1926) left the reading public in shock with its salacious details of homosexual lovemaking as a teenager under the dining table with the concierge’s son and as an adult atop the sand dunes with an Arab youth in Algeria.

Gide met up with Oscar Wilde and his lover Lord Alfred Douglas while in North Africa, and their friendship influenced his subsequent writings, which exalted honesty, openness and sincerity. Gide was one of the few people willing to defend Wilde’s literary reputation in the years after the Englishman’s death.

"One does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time."

In 1916 at the age of forty seven Gide fell in love with 16-year-old Marc Allégret (in photo at right), whom he adopted, and the couple eloped to London to commence an eleven year relationship. Marc was to fall briefly under the spell of Jean Cocteau, whom Gide feared would "corrupt" him. After the notorious affair with Gide, Allégret went on to establish a successful career in cinema, becoming a noted screenwriter and director of more than 50 films.

“My faith in communism is like my faith in religion: it is a promise of salvation for mankind. If I have to lay my life down that it may succeed, I would do so without hesitation.”

As a distinguished writer sympathizing with the cause of communism, Gide was invited to tour the Soviet Union as a guest of the Soviet Union of Writers. The tour disillusioned him, however, and he subsequently became quite critical of Soviet Communism.

“It is impermissible under any circumstances for morals to sink as low as communism has done. No one can begin to imagine the tragedy of humanity, of morality, of religion and of freedoms in the land of communism, where man has been debased beyond belief.”

Gide lived in North Africa during WW II and soon thereafter returned from Tunisia to Paris, where he died in 1951 at the age of 81. The following year the Catholic church included all of his literary works on the index of Forbidden Books.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Steve Gunderson

Seven months after this incident, Gunderson made his sexual orientation official in a New York Times Magazine profile published in October 1994, just before he was solidly reelected. The piece bore the headline: Fiscal Conservative. Social Moderate. Gay. The article included a quote by Newt Gingrich – "He's not liberal enough for the gay community, and he's not straight enough for the conservative community."

Elected to congress at the age of 29 after abandoning his desire to become a sports broadcaster, Gunderson struggled for many years to come to terms with his attraction to men. In 1983 the 32-year-old Gunderson walked into Badlands, a gay disco near Washington's Dupont Circle and eyed Rob Morris, a 23-year-old architecture student. "For me," Gunderson said, "it was love at first sight." Within a year they were living together in a relationship that lasted more than fifteen years. They co-authored the book House and Home in 1996. Today Morris is owner of a builder/architectural firm based in McLean, Virginia that specializes in Arts & Crafts designs.

In 1991 bad-boy activist Michael Petrelis approached Gunderson in an Alexandria, Virginia gay bar that the Congressman frequented. Upset that Gunderson had refused to co-sponsor the federal gay rights bill, Petrelis loudly and rudely urged Gunderson to come out and support gay rights and federal financing for AIDS research. Gunderson replied, “I am out. I'm in this bar, aren't I?” – brushing Petrelis off. The activist grew angry, threw a drink in Gunderson's face, and called the police on himself in order to garner publicity over the incident. The story appeared in the local press, and the papers back in Milwaukee picked it up and printed it. In spite of the scandal, he kept his House seat and was subsequently reelected.

Gunderson was an influential leader in other human rights causes, as well. His efforts on behalf of the ethnic Asian Hmong people resulted in the overturn of the Clinton administration’s policy of forced repatriation that often led to persecution ; as a result thousands of Hmongs were granted U.S. immigration rights.

Since leaving Congress after serving eight terms, Gunderson has been a vocal supporter of gay rights causes. He once read the names of AIDS victims with his former partner Rob Morris in memorial services on the National Mall in Washington. In January, 2010, he was appointed by President Barack Obama to the President's Commission on White House Fellows. Gunderson currently lives in Arlington, Virginia, with his partner Jonathan Stevens, director of demographic change for the Bertelsmann Foundation's North American office.

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

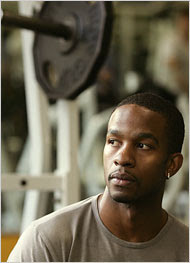

Wade Davis

Last September I wrote a post suggesting that the Washington Redskins might be the gayest NFL team ever – at least four players and an assistant General Manager of the Washington Redskins football team are known to be gay. Here’s the link:

http://gayinfluence.blogspot.com/2011/09/dave-kopay-jerry-smith-nfl-team-love.html

Wade Davis, a former cornerback for the Washington Redskins, spoke out publicly this week about his experiences as a closeted gay man playing in the NFL, while doing interviews with Out Sports and SB Nation. Davis, who retired from pro football in 2004, says he never told any of his teammates that he was gay while still on an NFL payroll for fear of jeopardizing his relationships on the team. “You just want to be one of the guys, and you don’t want to lose that sense of family…Your biggest fear is that you’ll lose that camaraderie and family,” Davis told Out Sports. To date, no active NFL player has come out, although a recent series of interviews with some of the game’s biggest stars reveal that historically chilly attitudes towards the LGBT community may be thawing throughout the professional sports world.

On his coming out: "There was a part of me that was a little relieved because, when I knew pro football was over, my life would begin," Davis said. "I had this football life, but I didn't have another life away from that. Most of the guys had a family and a wife, but I had football and nothing else." He says he first realized he was gay in 11th grade. "I can remember being in gym class and having the desire to look at a boy in a way that I should look at girls," he said.

After Davis left the NFL, he became a personal trainer at New York Sports Club in Manhattan and served as the Director of Player Development for the New York Gay Football League. These days he's a staff member at the Hetrick-Martin Institute*, which serves LGBT youth in New York City. “It’s the first job since football that I wake up excited for work,” said Davis, who also does campaign work for President Obama. “For these kids, the question isn’t whether they are shooting a basketball well, it’s whether they have a place to sleep tonight, whether they’ve eaten today.”

*Hetrick-Martin Institute youth range in age from 13 to 21, and many of them have been forced from their homes due to conflicts over sexual orientation. Hetrick-Martin provides an alternative safe space every weekday from 3:00-6:30 pm for program activities, job-readiness training and education. In addition, more than 5,000 hot dinners were served last year. Hetrick-Martin’s skills building workshops, internship programs, and performances are all designed to improve their participants’ chances for a healthier, richer future.

Here’s the complete interview with Davis:

Wade Davis, a former cornerback for the Washington Redskins, spoke out publicly this week about his experiences as a closeted gay man playing in the NFL, while doing interviews with Out Sports and SB Nation. Davis, who retired from pro football in 2004, says he never told any of his teammates that he was gay while still on an NFL payroll for fear of jeopardizing his relationships on the team. “You just want to be one of the guys, and you don’t want to lose that sense of family…Your biggest fear is that you’ll lose that camaraderie and family,” Davis told Out Sports. To date, no active NFL player has come out, although a recent series of interviews with some of the game’s biggest stars reveal that historically chilly attitudes towards the LGBT community may be thawing throughout the professional sports world.

On his coming out: "There was a part of me that was a little relieved because, when I knew pro football was over, my life would begin," Davis said. "I had this football life, but I didn't have another life away from that. Most of the guys had a family and a wife, but I had football and nothing else." He says he first realized he was gay in 11th grade. "I can remember being in gym class and having the desire to look at a boy in a way that I should look at girls," he said.

After Davis left the NFL, he became a personal trainer at New York Sports Club in Manhattan and served as the Director of Player Development for the New York Gay Football League. These days he's a staff member at the Hetrick-Martin Institute*, which serves LGBT youth in New York City. “It’s the first job since football that I wake up excited for work,” said Davis, who also does campaign work for President Obama. “For these kids, the question isn’t whether they are shooting a basketball well, it’s whether they have a place to sleep tonight, whether they’ve eaten today.”

*Hetrick-Martin Institute youth range in age from 13 to 21, and many of them have been forced from their homes due to conflicts over sexual orientation. Hetrick-Martin provides an alternative safe space every weekday from 3:00-6:30 pm for program activities, job-readiness training and education. In addition, more than 5,000 hot dinners were served last year. Hetrick-Martin’s skills building workshops, internship programs, and performances are all designed to improve their participants’ chances for a healthier, richer future.

Here’s the complete interview with Davis:

Monday, June 4, 2012

Farley Granger

Bisexual actor Farley Granger (1925-2011) made his mark in the Alfred Hitchcock psychological thrillers Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1951), both movies with gay subtexts. Although he carried on a number of scandalous affairs with both men and women, unlike most other actors who were gay or bisexual, Granger refused to marry to keep his fans and studios off the scent of his male relationships. When studio bosses berated him for being seen having dinner with composer Aaron Copland, a known homosexual, he shot back, “(Copland is) one of the most important composers in America, a gentleman I met at this studio when you hired him to write the score for The North Star,” which was Granger’s debut film (1943). “I’m not going to be told...who I can or cannot see in my private life.” Granger turned on his heels and walked out of Sam Goldwyn’s office.

Granger had been scouted at age 17 by a studio rep for Goldwyn and had featured roles in the The North Star and The Purple Heart (1944) before going into the Navy a few days after he turned 18. Still a virgin at age 20, he found himself stationed in Honolulu. Determined to change his status, he enjoyed a lovely night of love-making with a hostess at a private club. Before he left the premises, however, he was seduced by a handsome, older Naval officer, thus losing his virginity “twice in one night.”

This is not wishful thinking on the part of a biographer repeating an unconfirmed rumor. The source is Farley Granger himself, who wrote a tell-all memoir titled “Include Me Out” in 2007 (available in e-reader formats).

After his discharge from the Navy, Granger moved back in with his parents in California. Soon thereafter, he fled their alcohol-fueled bickering to move in with openly gay screenwriter Arthur Laurents, with whom he had a four-year affair. "As striking as Farley's looks were," Laurents related in his autobiography, "he seemed unaware of them. Once you knew him, what you marveled at was his sweetness. He was generous with praise for his peers and with presents for friends, as though he himself wasn't enough to give."

Thus began a life-long pattern. Although Farley had multiple affairs with women – most notably Shelly Winters, whom he called “the love of my life and the bane of my existence” – he lived with men. One of them, writer and soap-opera producer Robert Calhoun, remained his partner for 45 years, until Calhoun’s death in 2008.

Jane Powell being ignored by Granger (left) and Roddy McDowall.

Granger’s memoir details his affairs with several women, including Ava Gardner and Patricia Neal, but he reveals that his only serious affair with a female was with Winters. Granger worked during the golden age of Hollywood and counted among his friends and colleagues Charlie Chaplin, Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor, Judy Garland, David Niven, Jimmy Stewart, Hedy Lamarr and Jerome Robbins. He danced and sang opposite Barbara Cook in a revival of The King and I. This memoir is a pleasure to read, as he shares tales of his love affair with Italy while delivering the inside scoop on major film and stage projects.

Granger made Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) shortly after his military service, on loan-out from Goldwyn. In his memoir he laments the casting of James Stewart. Granger thought the film would have worked better with an actor who could show a more sinister bent, such as James Mason.

Two years later, while shooting a film on location in Manhattan, Granger had a two-night fling with composer Leonard Bernstein, who was so smitten that he invited Granger to join him on his upcoming South American tour. The two men remained lifelong friends.

Granger met his long-term partner Robert Calhoun (on right in photo below) while working on a stage production in 1963. The two slept together for the first time in Philadelphia on the night of JFK's assassination. They remained together until Calhoun's death from lung cancer.

Unhappy with the direction his career was taking, Granger bought out his studio contract and traveled to Italy to star in Luchino Visconti's film Senso* (1954). In his memoir Granger calls this his favorite role and one of his three best movie-making experiences. He made more films after returning to Hollywood, but he was never happy with the studio system and its relentless pressure to conform to the supposed expectations of the audience. In 1955 he moved to New York to act on stage. Although Granger’s greatest legacy is as a movie actor portraying low-life film noir characters, he preferred the direct link to an audience that stage acting offered.

*Granger’s memoir Include Me Out contains scores of insider film anecdotes. While shooting Senso in Italy in 1953, Granger hosted a traditional American Thanksgiving meal in Venice. He invited the cast and director (Luchino Visconti) to have their first taste of cranberry sauce and mince pie (neither was a hit). But the conversation during a postprandial game of Truth or Dare kept things lively. The wife of Massimo Girotti (1918-2003; known as the Italian Paul Newman – see photo at left) teasingly asked Visconti when was the last time he had sex. Without missing a beat, Visconti replied, “Yesterday afternoon with your husband, my dear.”

Granger also appeared in the soap operas As the World Turns and Edge of Night, popular television hits that were produced by his partner Robert Calhoun.

Granger died of natural causes a year ago, on March 28, 2011, at the age of 85, five days after Elizabeth Taylor. Unfortunately, Miss Taylor’s demise stole all the thunder from the press, and Granger’s death was given less notice than it deserved.

A 25-year-old Farley Granger in a short romantic scene from Strangers on a Train:

The three films Granger said he was most proud of (in chronological order):

They Live by Night (1947 – Nicholas Ray) film noir: a tale of two doomed young lovers on the run in small-town middle America during the Depression. Hitchcock cast Granger in Rope (1948) based on his performance in this film. It was Granger who suggested Cathy O'Donnell as his co-star. Granger and O’Donnell had little acting experience between them, and this was Nicholas Ray’s first feature-length film. This movie has a 100% fresh rating on rottentomatoes.com.

Strangers on a Train (1951 – Alfred Hitchcock) a classic tale of suspense that returned Hitchcock, after a string of failures, to the forefront of film making. Based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith, perhaps best known for The Talented Mr. Ripley, this film stars Granger as amateur tennis player and aspiring politician Guy Haines. While traveling on a train he is introduced to psychopath Bruno Anthony, portrayed by Robert Walker, who suggests they swap murders, with Bruno killing Guy's wife and Guy disposing of Bruno's father. As with Hitchcock’s Rope, there was a homosexual subtext to the two men's relationship.