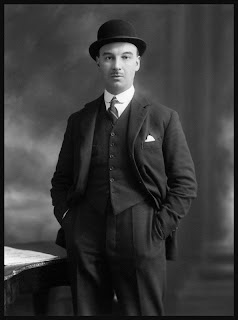

Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson (1883-1950)

The fourteenth Baron Berners was an eccentric British aristocratic man of leisure, who was also a painter, diplomat, chef, novelist and composer of classical music. Above all an aesthete, his contemporaries described him as short, bald and witty, a “mixture of sweetness and malice.”

He was born in into a family with a long noble pedigree. As a shy and effeminate only child, he was discouraged from advancing his love of art and music by a pious, staid mother, who felt such pursuits were unbecoming to a man of his class. Instead, she desired, more than anything, for him to become skilled at horsemanship. The eccentricities Berners displayed started early in life. Once, upon hearing that you could teach a dog to swim by throwing him into water, young Gerald concluded that by throwing his mother's dog out the window, he could teach it to fly. After being punished as a small boy by being closed up in a cupboard, he retaliated by locking all the bathrooms in his parent’s house and throwing the keys into a pond.

Berners was educated at Eton and entered the diplomatic service in 1899, despite failing the qualifying examinations. Among his assets, however, were fluency in both Italian and German. He was first posted as an honorary attaché to the British Embassy in Constantinople and was subsequently stationed in Rome, where he became a friend of author Ronald Firbank and composer Igor Stravinsky, who admired his musical efforts.

In 1918 Gerald inherited his uncle's title, fortune, and properties at the age of 35. Consequently, he left the diplomatic service and retired to an estate at Faringdon, twelve miles west of Oxford, in order to devote his life entirely to the pursuit of his pastimes and pleasures. Berners bought Faringdon House, a Palladian style manor, in 1919 and gave it to his mother for her lifetime use, keeping only modest quarters for himself. He spent most of the 1920s in London leading an amiably flamboyant existence, while also keeping a house in Italy.

With the death of both his mother and stepfather in 1931, the Faringdon manor house caught his imagination. Because it was more accurately described as comfortable than glamorous, Berners set about transforming it, creating a masterpiece of an English country house. On the walls Berners hung important paintings by Corot, Constable and Matisse. The 54-ft. drawing-room afforded fine views through five French windows beyond the fountain to one of the longest vistas in England, extending 22 miles across a patchwork English landscape.

As Lord Berners, Gerald cultivated a well-deserved reputation as an eccentric. When he was not dabbling in composing music, writing or painting (which he called “my little hobbies”), he read an enormous amount. He was known for such antics as dyeing the doves on his estate various colors, arranging color-coordinated meals (more often than not the food and dove colors matched), and traveling across Europe with a fold-away piano keyboard in the rear seat of his Rolls-Royce. He also frequented many of the literary and artistic salons of the day, and counted Evelyn Waugh, Cecil Beaton, the Mitford sisters and the Sitwells among his friends and guests. He once invited a friend’s Arabian stallion to join them in the drawing-room for afternoon tea. I’m not making this up.

Lord Berners (above) in the drawing room of Faringdon House, painting a portrait of his favorite horse, which had been brought into the room for the occasion.

The list of oddball behavior goes on. He sent the following invitation to Sybil Colefax, noted for her aggressive social climbing:

“I wonder if by any chance you are free to dine tomorrow night? It is only a tiny party for Winston and GBS*. I think it important they should get together at this moment. There will be no one else except for Toscanini and myself. Do please forgive this terribly short notice.”

The cruel joke was that Berners made both his name and the address on the envelope completely illegible.

*George Bernard Shaw

Even while entertaining extravagantly, Berners still found time to pursue his various artistic careers. As a composer, he was largely self-taught; nonetheless, he produced a body of work that Stravinsky praised. Berners was also friends with composer Sir William Walton, and Walton dedicated his popular Belshazzar's Feast to him. His best known and most enduring works, however, are his ballets, particularly The Triumph of Neptune (1926), commissioned and produced by Diaghilev and choreographed by Balanchine. His ballet A Wedding Bouquet (1936) had placards containing words penned by Gertrude Stein (shown with Berners at right). Lord Berners also commissioned Stein to write an opera libretto for Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights, but he never got around to composing music for it. As well, Berners wrote the soundtrack for the 1947 film Nicholas Nickleby.

Berners also wrote three volumes of autobiography and a number of short, campy Firbankian novels. In the 1930s Berners enjoyed a brief vogue as a painter, and his landscapes sold for extraordinary prices.

For twenty years, Berners lived openly with a man thirty years his junior, the equally eccentric Robert “Mad Boy” Heber-Percy (1911-1986). Before taking up with Lord Berners, Heber-Percy flunked a career in the cavalry, acted as a Hollywood extra, was sacked as a waiter for sloshing soup over a customer and helped run a notorious London nightclub. In 1934, Berners had a "folly" tower, perhaps the last such structure built in England, erected on his estate as a birthday present for his "Mad Boy." When asked what purpose the 140-ft. tower served he explained, “The great point of the tower is that it will be entirely useless.” A notice at the entrance read: "Members of the Public committing suicide from this tower do so at their own risk.” Despite Heber-Percy's short-lived wartime marriage to a woman, Berners left him his manor house (Faringdon House, c. 1780), his estate and fortune upon his death on April 19, 1950. “Mad Boy” Heber-Percy lived there himself until his death in 1986. It is now owned by Heber-Percy’s granddaughter, who is based in Rome. Faringdon Manor is available for rent by the month; recently a Texas couple took up residence there for a year.

When it came to food, Lord Berners was a masterful host, and his superb meals were sometimes overwhelmingly luxurious. One of Lord Berners’ best known dishes, Roast Chicken in Cream, was even included in The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book (1954), an immensely entertaining memoir/recipe compilation.

Berners died at sixty-six, a fairly peaceful death, not in the least fearful of what lay beyond. The doctor who had attended Lord Berners during his last years refused to send a bill, saying that the pleasure of his company had been payment enough. All his life Lord Berners had lived on the strength of his charm.

Baron Berners’ epitaph on his gravestone reads:

Here lies Lord Berners

One of the learners

His great love of learning

May earn him a burning

But praise to the Lord

He seldom was bored

Most of the information for this post comes from Mark Amory’s biography, “Lord Berners: The Last Eccentric” (1998).

There is a good deal to be said for frivolity. Frivolous people, when

all is said and done, do less harm in the world than some of our

philanthropists and reformers. Mistrust a man who never has an

occasional flash of silliness. - Lord Berners

Role models of greatness.

Here you will discover the back stories of kings, titans of industry, stellar athletes, giants of the entertainment field, scientists, politicians, artists and heroes – all of them gay or bisexual men. If their lives can serve as role models to young men who have been bullied or taught to think less of themselves for their sexual orientation, all the better. The sexual orientation of those featured here did not stand in the way of their achievements.

No comments:

Post a Comment